|

|

|

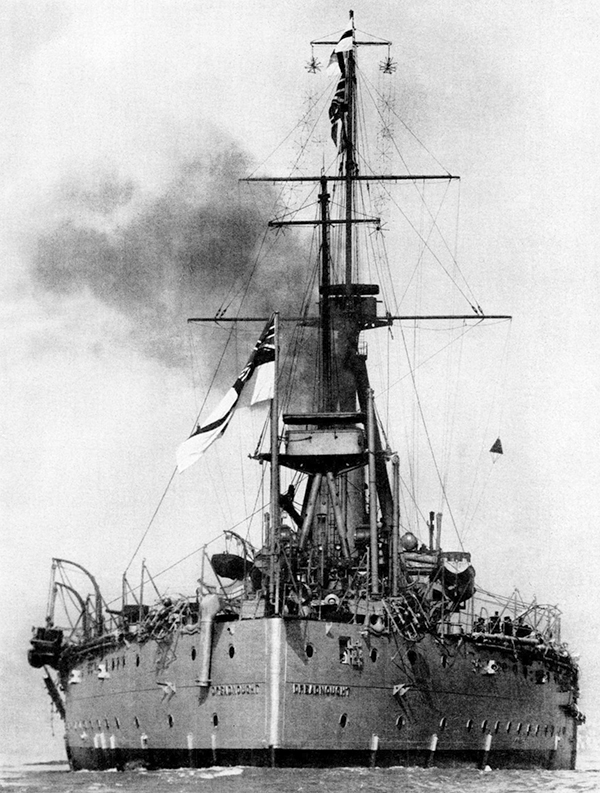

In the first decade of the twentieth century a dramatic revolution befell the world's navies. Great Britain, the world's preeminent sea power, launched a single ship that changed both the face of naval warfare and the balance of power in Europe. Even to the casual observer, HMS Dreadnought appeared distinctly different from all battleships that preceded her. Ten massive, 12-inch guns mounted in twin turrets, and the near absence of secondary armament, stood in stark contrast to the standard warship design of the day. Combined with several other innovations, the ship was so revolutionary that her birth instantly rendered the world's battle fleets obsolete�including Britain's own. All existing ships quickly became known as "pre-dreadnoughts," while this new class of warship bore the name of the British namesake�"dreadnoughts." Dreadnought's instant superiority to all previous warships was accomplished by removing nearly all smaller caliber weapons and replacing them with as many 12-inch guns as the ship could hold. Earlier ships were equipped with a tiered arrangement of guns of varying sizes. Small and medium-caliber guns were set within a "casemate"�an armored box placed amidships and oriented to deliver coordinated broadsides reminiscent of the days of wooden warships firing iron shot, while larger guns were placed in turrets forward and aft. But by their very nature, bigger guns had longer range, and the genius of Dreadnought's all-big gun configuration was her ability to bring all her guns to bear on an enemy at superior range. This revolutionary armament concept made the ship capable of lofting a larger broadside at distance than any other ship afloat�she became the equivalent of two, or even three, of her rivals. In this new order of battle, using big guns at long distances, the smaller guns of the pre-dreadnoughts were useless. The ship with the largest number of big guns could deliver more shell weight on target, at greater range and, at least on paper, was considered the de-facto victor even before the battle took place. Combining this massive firepower with thicker armor plating to resist enemy shells, and steam turbine engines giving her an unmatched speed advantage over adversaries in combat, allowed her to dictate the terms of an engagement with the enemy. Every seafaring nation now needed dreadnoughts, and they needed them fast. New ships were laid down at an ever-increasing rate, stretching each nation's treasury to the breaking point. The ensuing arms race was both a blessing and a curse; precisely because Dreadnought was so revolutionary, she temporarily leveled the naval playing field among nations. Germany's Kaiser Wilhelm II had long lusted for a powerful, world-class navy that could compete with Britain's�the launching of Dreadnought gave him a window of opportunity to achieve that dream. Britain's long-standing policy, being an island nation and dependent upon sea-borne trade, was to maintain a navy superior to the combined naval strength of the next two greatest sea powers, but with Dreadnought she had rendered her own fleet obsolete. This revolution in naval design swept up the supporting ships in the fleet as well. Armored cruisers gave way to battlecruisers�fast and nimble ships with lighter armor than battleships, but packing the same large caliber guns�fleet-footed warriors that could destroy anything other than a full-up dreadnought, but able to outrun those with their superior speed. Torpedo boats gave way to more powerful destroyers, and new "light cruisers" filled the gaps and protected the monster dreadnoughts from torpedo boat attack. Newly built fleets of these powerhouse ships enabled nations to project power far beyond their borders, threatening one another's security and leading to a rapidly escalating arms race that helped cause what is arguably the most violent armed conflict humans had ever unleashed upon themselves. These massive fleets, bristling with raw power and speed, left a trail of destruction in their wake�broken ships, wreckage and human lives�strewn across the sea floor around the European continent and beyond�a sprinkling of historical bread crumbs begging to be explored. |  |

| HMS Dreadnought...the Ship that Started an Arms Race |

| |

| 1/350 scale model of HMS Dreadnought | |

|

When the sparks arrived that ignited the European tinderbox, the world waited breathlessly for the expected clash of the great dreadnoughts. Such conflict was not to be taken lightly, however. Winston Churchill, writing after the war, referred to Admiral John Jellicoe, commander of the British fleet at Jutland, as "the only man on either side who could lose the war in an afternoon." Such was the importance of the great fleets these warring nations had built. Both Britain's Grand Fleet and Germany's High Seas Fleet entered the game cautiously. The first significant naval encounters took place at Heligoland Bight (1914) and Dogger Bank (1915)�but these were mere brushing engagements compared to what would follow at Jutland (1916). | |

|  |

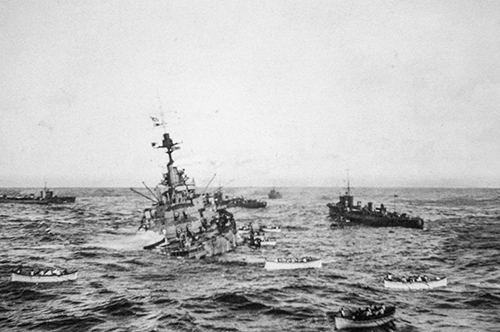

| The British King George V class dreadnought HMS Audacious | HMS Audacious sinking off Malin Head Ireland after striking a German laid mine, highlighting the lack of underwater protection built into these behemoths |

|

The great dreadnoughts, designed to unleash violence upon their enemies, would themselves succumb to the very violence their inventors had imagined. Armed with the most massive naval guns yet created, and armored with steel plate thick enough to resist plunging, high explosive shells fired by the enemy, the warships had a peculiar but unavoidable vulnerability. Such massive ships could only carry so much weight�the heavy armor and guns challenged their ability to remain afloat, and weight had to be trimmed somewhere. Below the waterline their unarmored hulls were like thin-skinned balloons awaiting the slightest pinprick to let the sea rush in. The German Navy had invested in submarines before the war in an attempt to compete with Britain's superior naval fleet and geographic advantages. When war came, mines laid by both submarines and surface ships were an enormous menace to merchant shipping�and to the thin-skinned underside of naval warships. On October 27 1914, only three months after the war had begun, the British dreadnought HMS Audacious struck a single German mine north of Ireland, puncturing her soft underbelly. Compartments near the explosion flooded immediately and the ship quickly took on a list; while the remainder of her hull flooded slowly, the sea inside her rose unremittingly. A variety of ships took turns trying to tow her toward Lough Swilly in Ireland after her engines gave out, but that single mine had doomed the giant dreadnought; fortunately, her entire crew were safely evacuated before she finally rolled over and sank off Malin Head, Ireland. | |

| * * * | |

|

August 2004: Ninety years later Mike Boring and I joined a group of British divers aboard Loyal Mediator out of Oban, Scotland. Our departure for Malin Head was delayed by a gale, however�the remains of hurricane Alex that I thought I'd left behind, had followed me across the Atlantic! Fortune was with us, however, and after two days the wind dropped out and we found ourselves in the open Atlantic headed for Ireland on a calm sea with only a touch of ground swell. A pretty sunset and a passing minke whale set the stage for a peaceful crossing and a spectacular dive the following day. | |

|  |

| One of the forward barbettes towers over the collapsed forward section of Audacious' hull | Part of a boiler sits atop the rubble of the ship's midship section |

| |

| Audacious' massive forward 13.5-inch guns stretch across the ocean floor | |

|

HMS Audacious lies upside down, as most capital ships do, in 207 feet (63 meters) of marvelously clear water�the remnant of the Gulf stream crossing the Atlantic. Dropping down the shot line, we are greeted by her inverted, riveted hull, looking like a slaughtered steel whale lying prone on the ocean floor. Swimming toward the bow over her curved bilges, the hull begins to break down into a rubble field. In the distance, a circular, tower-like form materializes in the depths�one of the forward barbettes: the armored foundation for the main gun turrets. As the rubble gives way to a gravelly, hard bottom, directly ahead sits an inverted turret, while off to the left stands another towering barbette. Approaching the gun turret is like stepping back in time: twin, side-by-side, 13.5-inch guns protrude from the massive circular structure, pointing nearly straight ahead as they stretch across the bottom. Open muzzles gape at the surrounding seascape, speaking of the great power of these behemoths. It is difficult to imagine the destructive power of the shells that these guns threw�1400 pound high-explosive projectiles, traveling faster than the speed of sound with a range of more than ten miles. At the end of their high-speed flight, the shells came crashing down on another deadly dreadnought�inhabited by men. The thought is frightening. The remainder of the dive is almost a letdown�nothing can compare to the sight of that forward turret and its deadly guns. There is a certain sadness to the dive as well, for the once great ship is now dead, merely a museum display of the great power of the once-mighty dreadnought. | |

|

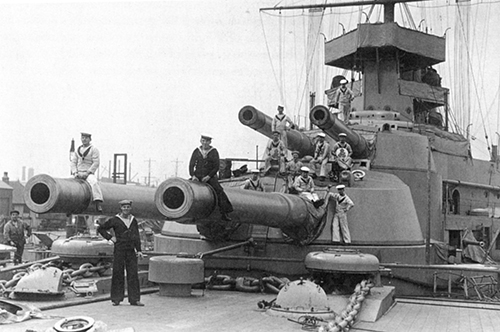

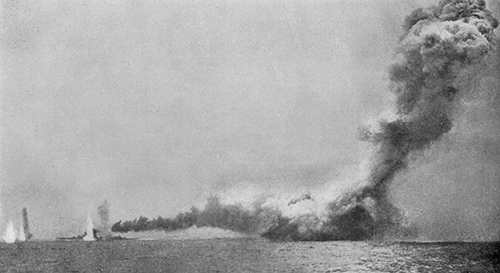

The great dreadnought contest the world was awaiting finally occurred at Jutland, off the coast of Denmark in the North Sea�a twelve-hour contest that erupted on May 31-June 1, 1916. A titanic confrontation between the world's two greatest fleets, involving some 250 ships and 100,000 men, with each side desperately trying to destroy the other. In the end, 14 British and 11 German ships were sunk, while more than 8600 lives were snuffed out in a violent and confused action with twists and turns that are still be analyzed and debated. Ironically, not a single dreadnought was sunk during the battle. In one of the most dramatic encounters during a day and night of horrific confrontations, the British battlecruiser HMS Queen Mary was struck by a salvo of shells from the German ships SMS Derfflinger and Seydlitz, then quickly hit by two more shells. A small puff of smoke was seen by witnesses, followed by a deep red incandescence, and then an explosion so violent that the entire ship was torn in half and the roofs of her massive turrets blown more than 100 feet into the air. When the smoke cleared, all that remained was Queen Mary's stern; another explosion and that too disappeared, along with 1266 men. Like Indefatigable before her, and Invincible to follow, Queen Mary had fallen victim to a defect in the design and use of her ammunition feed system, which allowed incoming shells to set off a chain reaction from the turret down into her main magazine. High explosive shells and powder, stored deep in the battlecruiser's belly, ignited in a fireball of an intensity hard to imagine�an explosion that no living or inanimate creation of man could possibly survive. Watching from the bridge of his flagship Lion, Admiral Beatty uttered one of the most famous lines from the battle, if not the entire war at sea: "There seems to be something wrong with our bloody ships today." | |

|  |

| Sailors posing next to the HMS Queen Mary's massive forward guns | The end for HMS Queen Mary during the Battle of Jutland |

| * * * | |

|

May 2002: Fast-forward 86 years in time, and in exactly the location where Queen Mary met her dramatic end. Some 80 miles off the coast of Denmark, a group of divers aboard the 24-meter Loyal Watcher, an ex-Royal Navy tender converted to a dive vessel, are here to explore and touch history�the remnants of arguably the greatest contest between battleships in history. Mike Boring and I drop ten feet from the Watcher's deck into the icy North Sea�4 degrees Celsius (39 Fahrenheit)�and descend 200 feet (61 meters) down the shot line to the shattered hulk of steel that is the grave for 1266 men. We are not the first to tread this sacred place, and surely not the last visitors to pay our respects. The air of destruction is clearly evident everywhere; the upside down hull of the legendary battlecruiser's stern is split open like an over-ripe, rotting fruit, with unexploded powder canisters and high-explosive shells bursting from the riveted hull. Long-dead turbo-machinery lies exposed to the depths of the sea they once drove this ship so speedily through. Torn and ripped hull plates speak volumes about the destructive force of thousands of pounds of high-explosives lit-off by enemy shell fire�a catastrophic explosion that took the life of a ship, and thousands of men, all in an instant of time nearly a century ago. Lying in the sand on the port side is the inverted hulk of the aft 13.5-inch gun turret. Almost miraculously, sitting atop the massive structure is a 4-inch casemate gun; dwarfed by the larger weapon, this small caliber gun somehow landed atop the big turret as the disintegrating ship fell through the water column�a rain of steel and flesh into the primordial depths that spelled the end of life for so many. | |

|  |

| Mike Boring with one of HMS Queen Mary's small guns and armor | 13.5-inch shells and powder canisters bursting from Queen Mary's inverted hull |

|  |  |

| Bow 13.5-inch gun and turret | Massive turret barbette lying on its side (bow section) | Stern machinery wreckage |

|

The following morning, despite forecasts of an impending gale, we made a second dive on Queen Mary, this time on the ship's severed bow section. Once again the evidence of destruction is overwhelming. Another enormous turret lies upright, but canted, on the sea floor, with one of the 13.5-inch guns pointing upward at a 45-degree angle; the second gun appears absent save the breech, clearly seen inside through the missing roof. Nearby, two massive steel rings�the foundations for the great turrets�lie on their sides like gigantic archways towering over a field of scattered debris and rubble�all that remains of one of the fastest and most powerful ships fielded by Great Britain during the Great War. | ||

All images, text and content Copyright © Bradley Sheard. All rights reserved.