|

Alphabet Soup in the (North) Atlantic

| This article was originally published in issue 10 (2006) of Wreck Diving Magazine. |

Ingredients: |

Old ships of all types, preferable in various states of decay Large basin of water A sprinkling of salt to taste Storms, fog and cover of darkness A few assorted wars Human carelessness |

Add all ingredients in a large basin. Shake vigorously. Let age for 50-100 years before serving. | |

|

In the "old days," before many of us began wreck diving, identifying a newly discovered shipwreck was often a difficult task. In a certain sense today's divers are a bit spoiled--we "know" the names of many of the shipwrecks that we dive weekend after weekend--they have become common knowledge. How their names came to light are often fascinating historical adventures in their own right. The "old timers" of our sport tell stories about how they identified such-and-such a wreck after long hours spent in dusty libraries and archives. It is a well-known axiom among professional treasure hunters that most of the work of finding a treasure ship is done in the library before ever heading out to sea. This is often true for those of us seeking to discover history for history's sake as well. While the hard labor of research is not quite as much fun as the physical endeavor of diving to adventure, it's clear that it often pays rich rewards. | |

|

For sure, there are also tales of simple identifications, when a lucky diver spies a curved edge of bronze protruding innocently from a sandy bottom. Digging madly in anticipation of their precious find, a beautiful bell is pried from the clutches of the ocean floor and, when luck is on the finder's side, a name is discovered for what was previously unnamed. Indeed, many a wreck has been identified in just such a manner. Rick Jaszyn identified the freighter Durley Chine, previously known only as the "Bacardi wreck," in just this manner back in 1987. (Of course, there are odd variations of this theme as well--witness George Hoffman's recovery of the bell off the Balaena, an old sailing ship sitting in the "Mudhole" off the New Jersey coast. The name was clearly inscribed on the recovered bell, but to this day no trace of the ship which owned the item has been uncovered in any archive.) And then there's the now-famous story of the U-869, that mysterious German U-boat sunk where it shouldn't have been off the New Jersey coast. Lot's of diving and lots of painstaking research over seven long years--and the wreck was finally identified in 1997 with the recovery of a spare parts box. | |

|

All of these methods have been tried, and all have their success stories to bear testimony to their effectiveness. But they all have one thing in common--they're lots of work! I'd like to propose what I think is a much simpler method. This may seem absurd, bizarre, or even brilliant to various readers, but give it some thought before you reject it outright. So here goes--ready? I propose that you just swim up to the bow or stern, scrape away a few sea anemones, and read the name of the ship right off her side! I realize that traditionalists may be loathe to accept this proposed method of identification. Shhhh, if you listen carefully, you can probably here them right now........ "Where's all the hard work?" they'll surely grunt. "You have to pay your dues--it's not supposed to be that easy!" "We sure didn't do it that way back when I was diving wrecks!" But hey, this isn't a crazy idea--there's precedent here! I can name half-a-dozen wrecks where the name is clearly spelled out on the bow or stern. Don't believe me? OK, here goes: | |

|

Although their sinkings were separated by nearly five decades, the wrecks of the passenger liner Andrea Doria and the tanker Bow Mariner have at least one thing in common. Both are huge vessels and needed little in the way of identification by divers--their identities were obvious to anyone with a sprinkling of common sense. | |

|

The Andrea Doria needs no introduction to divers. Sunk in a collision 60 miles south of Nantucket Island on July 25/26, 1956, the demise of the great liner was fully documented by news photographers at the time--in fact Harry Trask won a Pulitzer prize for his series of photographs of the ship sinking. Only twenty-seven hours after she disappeared, Peter Gimbel and Joseph Fox dived to her grave site to document the corpse. What they found was an odd sight indeed, for the ship appeared in pristine condition, paint still gleaming, but lying immersed in that same liquid she was designed to float upon. Her identity was obvious and needed no official "identification," but for any who doubted, her name was clearly spelled out in big, brass letters at both the bow and stern. Those letters are still there, proudly declaring the famous ship's name, and anyone with the desire and ambition to scrape away the ubiquitous coating of sea anemones can see them and "identify" the wreck for themselves. | |

|  |

| Jeff Pagano scrapes the letter "E" clean on the Andrea Doria's stern (left); The Bow Mariner's name board on her bridge (right) | |

|

A much more recent wreck is that of the tanker Bow Mariner, which sank off the coast of Virginia much more recently: February 28, 2004. Like the Andrea Doria before her, the first to dive the wreck didn't need much evidence to identify her. Sitting upright on the ocean bottom, the first visitors found her paint still gleaming and window curtains fluttering in a slight current. It was pretty obvious what and who she was--there aren't too many huge, newly sunk ships sitting in that particular area of the ocean. But, for those diehard skeptics who wanted definitive proof, her name is clearly spelled out on a set of painted name boards on each bridge wing: Bow Mariner. There is, of course, still some mystery surrounding this particular shipwreck (it seems that all wrecks have some mystery associated with them). The mystery here is what, exactly, transpired on board that led to her sinking. That an internal explosion of some sort occurred is apparent, but the surviving crew has kept mum on exactly what happened. | |

|

So, there are two examples of sunken ships where their name is clearly spelled out for anyone adventurous enough to go look. OK, I have to admit that those letters had nothing at all to do with the wreck's identification--these two examples were "no-brainers," so to speak. But still, the names are there just the same, so the concept is sound. Here are a couple of more examples: | |

|

Back in the winter of 1942, shortly after the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor brought the United States into the greatest war in man's history, the US East Coast was under siege by German U-boats. Operation Paukenschlag sent five submarines to America to welcome the nascent combatant into the war. Ship sinkings off the unprotected coast would soon reach the rate of one per day and continue for nearly six months before the tide of the battle turned. The second ship to be sent to the bottom in this battlefield was the British tanker Coimbra, who met her demise at the hands of U-123 on January 15. | |

|

Poking around in a library one day long ago, I stumbled across a fascinating book entitled Deep Sea Photography. Apparently the US government, in an effort to map and identify the rapidly growing number of shipwrecks off the East Coast during the war, began a novel survey of wreck sites using "drop cameras." They simply went out to the wreck sites in a boat and lowered a specially designed camera and strobe on a rope--a kind of early predecessor of the modern and more sophisticated ROV--and took some pictures. It was a kind of hit-or-miss affair and the pictures were taken at random wherever the camera happened to land. | |

|

As I was turning the pages of this book I was shocked to find a black & white photograph of a ship's name--COIMBRA, on one of the pages. Apparently, this drop-camera effort had managed to photograph the name of the sunken tanker spelled out on her bow, completely at random! You have to ask yourself, what were the odds of that? (Years later I was talking with Gary Gentile, and he related how he had actually met one of the guys who had taken that remarkable photograph, and that he still had a framed copy of it on his desk!) | |

|

So here is an example where the wreck was actually identified by reading the ship's name off of her bow. Admittedly, it wasn't done by divers. Many years later we happened to be diving on what was now well-known as the wreck of the Coimbra; that black and white photograph still in my mind, I swam up to the bow and found that the letters are still there, (nearly) as they were when first photographed by the US government. The letters are welded steel, and the "C" has all but evaporated into the sea, but the remainder of her name is still there plain as day. | |

|  |

| The name Coimbra spelled out on the ship's bow (left); John Chatterton scapes the letters clean on the Sebastian's bow (right) | |

|

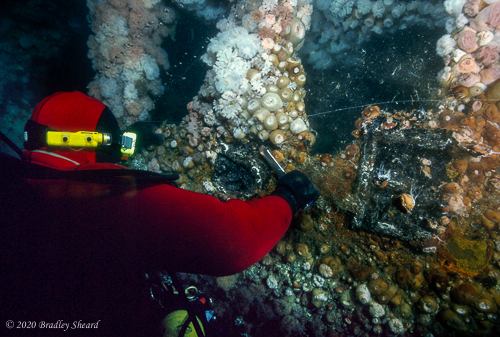

In the summer of 1994, John Chatterton and Dan Crowell started running some exploratory trips on-board the dive boat Seeker to find new shipwrecks. One idea was to explore some of the many "numbers" out by the wreck of the Andrea Doria. (Their idea was that any divers who bothered going out that far out ended up at the Doria, and any other "numbers" were probably unexplored.) One set of numbers yielded a large, upright ship that appeared to be an early oil tanker. The very first dive on the wreck found us tied into the ship's focs'le, where Gary Gentile promptly found her bell. A subsequent dive brought the prized artifact to the surface, where Gary carefully removed a thin veneer of marine growth before a captivated audience. Gradually a name appeared on the bronze bell: SEBASTIAN. | |

|

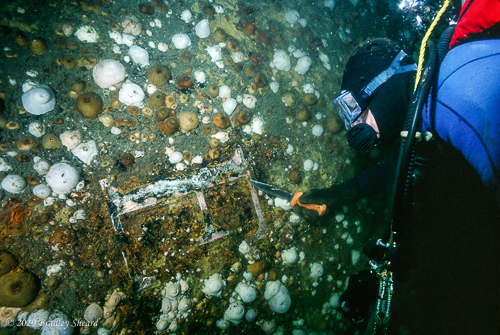

The ship's superstructure was leveled and covered in fishing nets; her stern deck sported a large-caliber gun emplacement, typical of those mounted to defend against U-boats during both World Wars. While most divers explored the area where the bridge once stood in search of trinkets, John Chatterton dropped over the side of the ship's bow, searching for letters of the alphabet. Applying the sharp edge of dive knife to the ubiquitous coating of sea anemones revealed the prize he was seeking--a set of brass letters spelling out the ship's name. The ship had already been identified by Gary's discovery of the bell, but in this case an alternative method of identification would have served equally well. | |

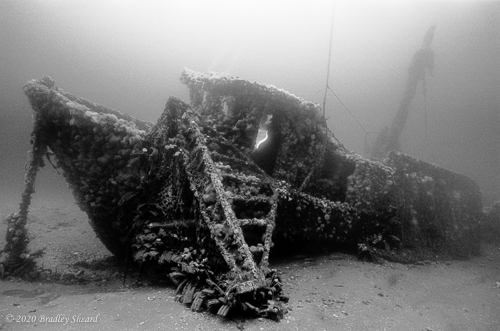

On July 3, 2004, a group of divers on board Harold Moyer's boat Big Mac out of Cape May, New Jersey, dived on a set of loran numbers--a fishing snag---in the hope of finding a new shipwreck. Descending through 190 feet of water we found a steel-hulled fishing trawler, sitting upright on the bottom and appearing largely undamaged. Encased in a fluffy shroud of sea anemones, the old fishing boat had a slight list to port. Hung-up on her port gunwale was a scallop dredge--perhaps lost by the skipper who first recorded her position after losing his gear. Her mast still stood proudly erect while a tangled mass of wire rigging and steel booms trailed off into the sand on the port side. | |

|  |

| The fishing boat Tomahawk sits upright on the ocean floor off New Jersey (left); a new wreck being born (right) | |

We had indeed found a new shipwreck, and now she needed a name. While we all reveled in our new discovery, Steve Gatto alone had the presence of mind to examine her bow in detail. Scraping through the heavy coating of marine growth solved one-half of this new mystery. Still visible in painted letters was her name: Tomahawk. All that now remained was to discover her story--who was she? How did she end up where she did? And perhaps most importantly, what had become of her crew? To date, although the name of the wreck is known, no trace of when she sank and what her story was has been uncovered. | |

Cruising back toward Cape May that afternoon, contemplating a newly discovered shipwreck and her mysterious demise, an ironic twist of fate led us into an encounter with yet another shipwreck from a slightly different angle. What at first appeared as a dark smudge on the distant horizon soon grew into an ugly black cloud and then a burning inferno on the surface of a twilight sea. There on a lonely expanse of ocean, some 45 miles from the safety of land, burned a fiberglass fishing boat; alongside floated an inflatable life raft with five shaken men staring in shocked disbelief at their boat. As we rescued the crew of the Santa Clara, we became part of a story that some future discoverers of a tiny shipwreck might someday search out in some dusty archive. | |

Ask a group of wreck divers what haunts their dreams and surely some lost passenger liner will rise to the top of the conversation. Why, you might ask? For some the fascination stems from the drama of human tragedy--perhaps on some Freudian level there is the inevitable link to the Titanic lurking in the darkness of the subconscious. For others it is the lure of trinkets and treasure that causes a subtle rise in the pulse. Each has their own reasons, but the allure is a common affliction. Along the Jersey shore the liner Carolina is one that brings a faraway look to the eyes of a diver who knows her story. For years many had spent summers searching and winters dreaming of finding her remains. How is it that a ship comes to collectively haunt a group of divers? Consider the following account of her demise as a brief introduction to a common longing. | |

Unknown to many, the Second World War was not the first appearance of German U-boats off the American coast, but the second. The First World War had brought a small group of adventurous submariners here in huge "U-cruisers" bent at preying on unprotected merchant shipping. In an age when submarines were in their infancy, crossing the broad expanse of the Atlantic was quite an undertaking; doing so to wage war on a foreign shore upped the ante considerably. | |

After the United States entered the war on April 6, 1917, the public waited expectantly for hostile U-boats to appear off the American coast. As month after month passed and the German raiders failed to materialize in American waters, the public fear of a U-boat invasion began to fade. More than one year would pass before the U-boats appeared off the Eastern Seaboard, but when the submarines did come, they arrived with a bang. | |

The first visible indication came on May 25, 1918, when three schooners were sunk off the coast of Virginia. The submarine responsible, U-151, had been built as a cargo carrier to break the British blockade of the North Sea, but was later converted to a long-range military submarine for extended operations in distant waters; her commander went by the elegant title Korvettenkapitan von Nostitz und Janckendorf. The U-boat had been present off the US coast for several days before sinking the trio of schooners, stealthily planting mines outside the entrances of both the Chesapeake and Delaware Bays. After announcing his presence to the world, von Nostitz began a rampage of destruction fit for the record books and did not leave the American coast before sending 26 ships to the bottom. Surely the submarines most successful day occurred on June 2, when she destroyed six vessels off the New Jersey coast--a date that has come to be known among divers as "Black Sunday" (a nickname coined by Gary Gentile in the first edition of his book Shipwrecks of New Jersey). | |

U-151 started the day by sending a steamship and two wooden coastal schooners to the bottom by noon: the steamship Winneconne was first, followed by the schooners Isabel B Wiley and Jacob M. Haskell. Not a bad breakfast for a submarine. A bit past three p.m. U-151 found and sank another defenseless schooner, Edward H. Cole, followed by the small steamer Texel, carrying a cargo of sugar, a couple of hours later. A large breakfast and late lunch had not spoiled the submarine's appetite for dinner, however, and the piece-de-resistance came around six p.m. when U-151 came across the New York and Puerto Rico Steamship Company's passenger liner Carolina. While the two freighters and three schooners encountered earlier in the day had been disposed of using a combination of bombs planted by boarding parties and shellfire from the submarine's deck gun, Carolina was apparently special. After the passengers and crew had abandoned the vessel, the Germans tried out one of their precious torpedoes on her. The torpedo proved defective, however, ran wild, and the German's were forced to finish off their prize using the deck gun. | |

For years divers dreamed of finding the sunken Carolina. On June 15, 1995, four divers and a fishermen combined their resources and the elusive Carolina finally gave up her secret location. Over the previous winter, John Chatterton had begun collaborating with a local New Jersey charter boat captain, Paul Regula. Together they sat down with a chart, loran numbers of fishing snags and the historical positions of the sinkings from U-151's log book. While none of the positions were exact matches, they began to develop a working theory as to which of the loran numbers corresponded to which shipwreck. That summer they would put their theory to the test. | |

Barely two weeks past the seventy-seventh anniversary of the Carolina's sinking, four divers descended 240 feet of anchor line to find the huge and decaying fantail of a ship, listing to port, on a sandy bottom. Portholes lay everywhere, along with a few bits of scattered white china. The wreck was clearly old, clearly large, yet just as clearly her identity was still a mystery. | |

After surfacing from the first dive, the five of us sat around the back of Paul's boat discussing the dive, what we had seen and what to do next. Every one of us felt that this had to be Carolina--but how to prove it? Everything fit--the close proximity to the historical sinking position, the size and appearance of the wreck--everything. I'm not sure which of us thought of the answer first, but as we sat around looking at historical photographs of the ship before she sank, one of us ponderously began with "I wonder.....you don't suppose that the name is still on the stern, do you?" We all looked at each other with sudden revelation--the ship was from an era where decor still mattered among ship owners, and brass letters proudly proclaiming a ship's name were common on freighters and tramp steamers, much less passenger liners. Suddenly identification seemed a real possibility! | |

Of the four divers on board, only John Chatterton had a sufficient surface interval to make a second dive that day, so it fell upon him to search for a name on the ship's stern before pulling the hook. While John made his dive, the three remaining divers and one fisherman sat anxiously on the boat, feeling somewhat like the lone Apollo astronaut remaining in orbit while his two companions walked on the surface of the moon. When John finally surfaced, the grin on his face was a mile wide and in his mesh goody bag was a large brass "C." The Carolina had been both found and identified! | |

|  |

| John Chatterton holds the letter "C" that identified the liner Carolina (left); part of Texel's name spelled out on her bow (right) | |

Meanwhile, another group of divers was also searching for Carolina. Diving a different set of loran numbers not too far away, a group led by Gene Peterson discovered an untouched old freighter sitting in 220 feet of water. Recovery of some china with the logo of the shipping company identified this ship as Texel--sunk by U-151 only hours before Carolina. Subsequent dives on this wreck found a set of brass letters as well, this time on the ship's upright bow section, spelling out "TEXEL." Those proud ship owners from the beginning of the century and their penchant for brass letters had unknowingly helped exploring divers from another era in rediscovering history. | |

| * * * | |

So you see, just occasionally, identifying a new shipwreck is simpler than reading tea leaves and as easy as reading the alphabet soup in the sea. The next time you're swimming around a newly discovered shipwreck, or an old but as-yet unidentified friend, take a look on the bow or the stern, underneath all that nasty marine growth--you just might find her name spelled out as clear as day! You may still need to go to the dusty-old library to find out her story--but at least you'll have a place to start looking! | |

All images, text and content Copyright © Bradley Sheard. All rights reserved.